19

Thirty Years With Miniature Roses

'Tis God gives skill, But not without men's hands: He could not make Antonio Stradivari's violin Without Antonio.

ANONYMOUS**(Southern Florist & Nurseryman December 4, 1964, p. 17)

I saw my first true miniature rose, Rosa rouletti, in 1935 and was so intrigued with this diminutive rose that I soon acquired several of my own. 'Tom Thumb,' and 'Oakington Ruby plants' were soon added to my collection. I enjoyed growing these miniatures but did little to develop new varieties from them as most gardeners of this era were unfamiliar with miniature roses and the market for them was limited.

However, I was growing numerous seedlings of other roses, some of which played important roles in the development of my miniature varieties. Of these, one seedling (later named 'Carolyn Dean') when crossed with 'Tom Thumb' produced the miniature rose 'Zee.' Using 'Zee' as the pollen parent the way was opened for the breeding of a number of my new varieties. We still use 'Zee' as a breeder for we have not yet exhausted its usefulness. Some offspring of 'Zee' ('Eblouissant' X 'Zee') produced several tiny flowered, tiny foliaged miniature climbers. Two were named and introduced'Fairy Princess' and 'Magic Wand.' In recent years we have discovered the breeding potential of 'Magic Wand' and so beginning With the 1964-65 season we started introduction of a whole new series of miniatures. Among them are 'Jet Trail,' 'Baby Darling,' 'Trinket' and others, With still more to come.

Several other seedlings have been (and still are) important in the origination of improved new varieties. Among these are an 'Oakington Ruby' X 'Floradora' seedling, several rambler type seedlings having Rosa wichuraiana as one parent, a red climbing floribunda seedling of complex heredity and several more of quite mixed heredity. A new tin-named moss rose hybrid is also being used. At least five species have at one time or another been included in my work with miniatures.

METHOD OF OPERATION: A short description of the methods and some of my reasons for using them may interest other plant breeders. As indicated earlier I seldom use a miniature as the seed parent. The reasons are several, but the most important is that many miniature varieties are female sterile or so nearly so that getting any number of seeds is discouraging. If seed hips do set they usually contain only one seed, rarely 2 or 3 and their percentage of germination is often very low.

The physical aspect of size is also a limiting factor. Plants are small and the tiny flowers present problems. Extra care must be exercised so as not to damage the delicate flower parts during the emasculation process. So for practical reasons, I have chosen to use those varieties (or clones) which are more easily handled. Because of their vigor, ease of working and ability to set seed hips, which contain not one but from 4 to 10 seeds, the breeding can be advanced much more rapidly.

One of the best (or at least most productive) varieties used as a mother or seed parent has been the yellow climber, 'Golden Glow.' Hybrids of this with 'Zee' or 'Magic Wand' have produced a number of good miniatures, among them 'Easter Morning,' 'Climbing Jackie,' 'Little Showoff' and 'Yellow Doll.' Most of the offspring are female sterile but some will produce a small amount of pollen.

Another very important and easily worked parent has been a seedling (Rosa wichuraiana X 'Floradora') known in our records only by number (0-47-19). The plant is a vigorous hybrid wichuaraiana type rambler resembling the old variety 'Dorothy Perkins.' Flowers are single (five petals) and borne in small to large clusters which cover the plant in late spring. The broad petals are a blend of soft pink and apricot shading into yellow at the base. Stamens are abundant but so evenly arranged that this rose is a joy to work. All five petals can be removed in one movement just before the bud opens. The pistils are tightly and evenly bunched so that placing pollen is easy. Best of all, seed hips may contain up to ten seeds.

But there are certain disadvantages in using climbers such as those described. If these mother plants were pure for the dominant climbing (or tall) factor we would not use them since all the offspring would be tall "once" bloomers. However, the ones we do use are known to be heterozygous for this factor; for example, they carry the gene (or factor) T for tallness (climber) and the recessive gene for dwarf (or bush) habit. Thus, to secure a new dwarf everblooming rose plant it is necessary to grow four times the quantity of seedlings that would be required were both parents bush (dwarf: tt) . But this is compensated for, in part, by the following reasons:

1. The selected fertile climber is much easier and faster to work.

2. More seeds can be produced more easily.

3. Hereditary combinations not otherwise possible are easily made.

4. These climbers can serve as bridges to reach more distant goals.

However, this is not the whole story. We are not looking for just a dwarf (bush type) everblooming rose but for a bush type everblooming miniature. To get this result one must cross our seed parent above (climber Tt) with a miniature rose. This becomes further complicated when a miniature climber such as 'Zee' or 'Magic Wand' is used as the miniature pollen parent. While both of these are everblooming climbers (and descendants of the everblooming polyantha climber, 'Carolyn Dean') there seems to be a linkage between this everblooming character and the bush factor. In breeding, such parents (although of climbing habit) seem to behave more like bush-type miniatures. To create a dwarf bush-type miniature we must combine parents which bring together all of the necessary basic genetic factors plus those of color, form, substance, etc.

The aim or goal of all my breeding has been to produce better miniature roses, not just something different. To me vigor, hardiness and ease of growing are most desirable. I want varieties of such vigor (this may or may not have anything to do with size of bush) that plants can be grown by almost anyone anywhere. They should not require babying or undue care. Hardiness implies more than just hardiness to winter cold. We also need kinds which can take extremes of heat which in many areas is much more of a problem than cold. Improved varieties should be able to tolerate such unfavorable conditions as over-alkaline soil and water, and smog.

They should be able to survive attacks of disease and insects. A good degree of tolerance to spray and fungicides is desirable. This does not mean that they will be immune to damage but that these "super varieties" will possess above average resistance.

Another goal for the future is the development of bushy, compact-growing varieties suitable for florist's pot plants. These should produce a saleable plant in a reasonable time at a cost which will make possible successful competition in the market. This special pot variety of miniature rose need not compete in price so much as in quality and customer desirability. Such varieties must be free flowering and produce heavy petaled long lasting flowers.

One cannot work intimately with anything without making certain observations and discoveries. Several things stand out in my work over the years dealing with miniature roses. One is that it would seem that this "miniature" phenomena should be a recessive. If this were true the "miniature factor" would have to come from both parents with the factor (s) for bigness giving way to the purely recessive factor (s) for miniature. But in practice this is not true.

In practice the miniature phenomenon appears to be controlled by a dominant factor (gene or genes) and this has been my approach to miniature rose breeding. If a large flowered rose variety is crossed with a miniature we get a high proportion of miniatures in the first (F1) generation. But no matter what size flower the seed parent has, the miniature influence on the offspring is not only discernible in small flower size but in several other characteristics as well. Some of these characteristics, such as flower and leaf size are relative, thus a hybrid tea X miniature would show larger (though miniature) flower and leaf size than would a cross of 'Ellen Poulsen' X miniature.

Other characteristics are reduced leaf size, in proportion to the flower, a multiple base branching habit in the seedling (similar to polyantha or multiflora but usually more pronounced) and total or near total female sterility under ordinary conditions. When seed hips are formed they are usually few and contain but one seed (sometimes two or three) which more often than not is not viable. Many of the seedlings (if not too double) will produce anthers from which pollen can be obtained. But clones (varieties) of miniatures, from which useful amounts of good viable pollen can be harvested, are relatively few.

Some have attributed this sterility to the fact that some of our hybrid varieties have an odd number of chromosomes. For example, the true or basic miniature forms such as Rosa roulettii, 'Oakington Ruby,' and a number of the newer small flowered (1 inch) varieties have 14 chromosomes; so do the tea roses, polyanthas, R. wichuraiana and many of its small flowered rambler type hybrids. Hybrid teas have 28 chromosomes, so when we take one-half from each parent ( 7 plus 14 equals 21) we should get offspring with 21 chromosomes and along with this unbalance, sterility. This is not always so but space does not permit further elaboration of this.

In Chapter I some of the history, discovery, and possible origin of miniature roses is given. I cannot accept this as the whole story, nor do I believe that Rosa roulettii necessarily is one of the older varieties rediscovered. In talking of this with Dr. Dennison Morey, a couple of years ago, he agreed with this view and had himself come to such a conclusion through reading of such fragmentary accounts as are available in the literature on roses.

Having worked extensively with miniatures for many years and grown more seedlings from a wider assortment of crosses than probably ever attempted at any previous time or place, certain observations have been made and conclusions drawn.

It would appear that miniatures really were never "lost" during that period between circa 1860 to 1917 when R. rouletti was found in Switzerland. H. B. Ellwanger wrote in his famous book The Rose (first published 1892, revised edition, 1912) as follows:

"What are called Fairy Roses are miniature Bengals (China roses) ; we do not consider them of any value, the Bengals are small enough."

In my own work several important and interesting seedlings or groups of seedlings have been observed over the years which may throw further light on the subject of origins. First, many years ago, before I had ever heard of a miniature rose, a very small flowered plant appeared in a lot of seedlings grown from a plant of climbing 'Cecile Brunner.' The seed hips had self-set naturally and the plant was away from other roses. A fairly large population was grown but most were once-blooming multiflora type plants with single or nearly single (five petal) flowers. Two or three resembled the parent and were everblooming; a few were low bushes. One plant of arching, climbing habit to about three feet had small foliage and tiny one-inch, double near-white flowers. Buds were tiny, about the size and shape of R. roulettii. Five or six plants were propagated but all were destroyed while I was away at college. Today this would be classed as a true miniature climber.

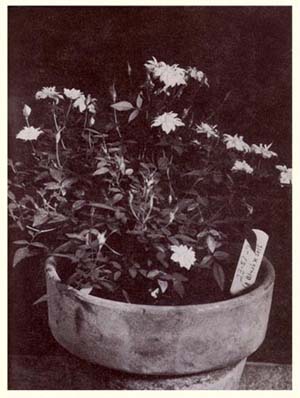

Next, some interesting seedlings resulted (see photo 19) when, several years ago, I crossed a plant of R. wichuraiana with 'Goldilocks' (F1) and also with a seedling which was half 'Goldilocks' (same yellow color but smaller flower). The R. wichuraiana X 'Goldilocks' cross produced a number of seedlings, all climbers, with flowers which ranged in size from about that of a nickel with a few up to that of a half dollar. Most were white to creamy white. Foliage was small to very small.

The second cross (R. wichuraiana X seedling [seedling polyantha X 'Goldilocks'l) produced many plants which were similar to the first. Flowers ranged from 3/4 to 1 inch in diameter, both single and double, on tiny rambler-type climbers which grew from 18 inches to 3 or 4 feet tall. Foliage was very tiny, in keeping with the miniature flower size. Again, almost without exception the plants produced no seed hips. As I recall only one plant from this lot (which I still have) produced seed and it has single 2 inch flowers. The others were destroyed when the space was needed.

More recently several lots of self-set seeds obtained from a plant of the China rose 'Old Blush' (Parsons' Pink China) supposedly in cultivation before 1759, were planted and the seedlings observed. In all three lots, gathered in different years, the germination was only fair to poor. But 'Old Blush' produces hips readily and each hip contains several medium size seeds. From the first lot quite a number of the seedlings were very definitely of the miniature type. One plant which has grown no taller than 10 inches in seven years has tiny leaves and tiny miniature pink buds opening to one-inch pink flowers (same color as R. roulettii) with seven or eight petals. It has on occasion set a few seed hips.

From the same lot also came other miniature roses ranging in height from 10 to 12 inches. Most of these were very bushy with double one- to one and one-fourth-inch flowers ranging in color from pale pink to medium rose-pink.

One of these produces orange colored hips containing one to three seeds none of which appears to contain an embryo. Another grew into a dense free blooming plant with flowers almost duplicating 'Pink Joy' (which is a self seedling of 'Oakington Ruby') . Cuttings of this plant were difficult to root. Still another one of these seedlings grew not over 8 inches high and bore soft pink double flowers resembling 'Peggy Grant.' Cuttings of this were also difficult to root.

The only seedling of the lot to be introduced was one which has slightly larger foliage and lavender-blue (or magenta) colored semi-double flowers. This selection, 'Mr. Bluebird,' grows readily from cuttings and has proven quite cold hardy. Some seed hips are produced, carrying up to five seeds, but germination is very poor. However, among its self seedlings have been several growing not more than 6 to 8 inches tall with miniature leaves and tiny double flowers usually not more than one-half to one-inch in size. Petals are usually very narrow (lance shaped) . No seeds have been observed on any of these seedlings but some pollen is produced.

In the first lot (1957) of 'Old Blush' seedlings one plant was a miniature climber which grew about 3 feet tall. Foliage was very tiny with individual leaflets about three-fourths-inch long. Flowers were single (five petals) light pink and about three-fourths-inch in diameter. Fewer seeds of 'Old Blush' were planted in the two more recent lots but results were similar. Now, what does this all mean, both in the matter of origin of miniatures and in their breeding?

In the first place, I do not believe that Rosa rouletti is as old as first suggested and generally accepted. We know that some of the old China varieties, probably including 'Old Blush,' 'Nemesis' (1836) , and others plus some of the old tea rose varieties, have long been grown in the balmy climes of Southern Italy and France. Dr. Dennison Morey has suggested that 'Nemesis' may be a seedling or sport of 'Pompon de Paris' (see The Miniature Rose Book, p. 140; Margaret Pinney, D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.). This might be true, yet this China variety may also have been the parent of some miniatures. It has also been suggested that 'Juliette' might be a dwarf sport of a large rose (even a hybrid tea) . To me it has considerable resemblance to 'Gruss an Teplitz of which it could be a seedling. But to confuse the issue, I have had some selfed seedlings of 'Oakington Ruby' which resembled 'Juliette.' One was almost a duplicate of 'Juliette' only the color was pink. It would have been an easy matter for someone living in Switzerland to have visited relatives in the Mediterranean area and to have carried rose hips home in pocket or purse. Seeds could have even been sent in a package or letter. This might have occurred any number of times. Seeds could have been planted in a pot or a window box. When harsh winter weather arrived, which plants would have been most likely saved? I think the smaller growing plant in a pot would have been the one, not just because it was so dainty and attractive but also because it could be more easily protected. If I have produced miniatures from a China rose ('Old Blush') the same thing could have been done by some Swiss gardener and the time might not have been any more than fifty or sixty years ago!

20. This interesting seedling ('Old Blush' X self) has tiny leaves, flowers under I inch and is a true miniature, but it is not descended from any miniatures as we know them.

So a logical question may be, "Was there ever a species (or sub-species) which could rightfully have been called Rosa chinensis minima?" I am inclined to think not. I cannot now believe that there ever was such a rose for several reasons.

In the foregoing I have set forth the results of many years of growing and observing miniatures. I have directed attention to the observed tendency to sterility (especially female) in miniatures no matter what their origin. It would appear that there is, or could be, some connection between this phenomena of miniaturization and sterility.

I have shown that miniatures can be, and have been, produced from the seedlings of certain varieties, such as 'Old Blush,' and also from crosses of dissimilar kinds as with my crosses of Rosa wichuraiana X 'Goldilocks,' etc. Yet another way could be by sports (or mutations) . I have not observed this, but there is one variety listed in Modern Roses VI which is claimed to have so originated. 'Baby Peace' (Plant Patent 2201) is claimed by its discoverers to be a sport of 'Peace' rose with a small one-half to one inch double flower, 50-55 petals, ivory-yellow tipped pink.

This brings up yet another often observed phenomenon known as witches'-broom. These dwarf, multibranched growths which occur quite often on conifers and other plants are an abnormal growth formation which may occur almost anywhere on a branch or tree. A number of dwarf ornamental conifers have been propagated originally from such brooms.

In a paper delivered at the 1964 annual meeting of the International Plant Propagators' Society, Eastern Region, Alfred J. Fordham from the Arnold Arboretum discussed a number of these witches'-brooms observed on pine and hemlock and reported on the behavior of seedlings grown from some of them. It was pointed out that cones were smaller and less abundant on the broom than on the normal parts of the tree. Also, certain of the broom seedlings were much smaller and slower growing, often with a marked tendency to branch thickly at the base of young plants. This similar tendency to base branching is one of the characteristics of miniature roses.

These witches'-brooms which appeared as if by magic without any apparent cause were, of course, baffling to observers in times past. Since the pattern of growth was so different and broomlike, it was only natural that simple country folk should see "the broom some witch had left behind."

Later it was thought that some virus or infection might be the cause. Then, with the growing knowledge of mutations (or sports) this seemed to be the answer. Cell studies indicated how such accidents of nature might initiate witches'broom mutations as well as others often observed in gardens and orchards.

But we must remember that mutations are not always good or desirable nor are they necessarily the step forward in the chain of life that so many think they are. In fact there are those who look upon most mutations as merely an aberration, a temporary straying from the norm. Nature does not like the stray and will even destroy it or allow it to die. It has often been observed in rose varieties which originate from sports, that there is a constant tendency to revert or return to the original color, size, or growing habit.

These sports, mutations or aberrations are usually quite basic in origin. That is, they start as a change in a single cell. But this does not necessarily mean that the cell has lost its directions. Only the message transmitted is garbled or temporarily masked.

Why is a miniature rose miniature? Is it because the instructions passed from one cell to another say "miniature," that is, they are dominant as earlier suggested, or is there a deeper reason? I stated earlier that in practice I proceed with my crosses as though a dominant factor or factors were the determining causes and it has produced results. But for a long time I have questioned this assumption and have thought it might be due to an inhibitor or some inhibiting influence which made the rose appear to react thusly.

We now know there is no such thing as a "simple" cell. Every living cell is a masterpiece, so complex that only recently have we begun to unravel some of its mysteries. It is a living organism which carries on the complex and interacting processes of life in order to perform its individual and "community" functions. And it contains within itself a "master tape" or blueprint with full instructions, of which a copy is passed on to each "daughter" cell.

So each cell has all these instructions carefully plotted and packaged. Within the nucleus of each cell are long threads (chromosomes) which contain DNA (Deoxyribonucleuic acid, a substance within the chromosomes of a cell) which in turn carries the genetic information (code or master tape) necessary for the replication of the cell and directs the building of proteins. Since any change must originate in a cell it is here at headquarters that orders for such change (mutation) are given.

But we know that all cells are not alike, even in the same organism such as a rose plant. Some are directed to form roots, others stems, leaves, or flowers. Others must play their part in seed and pollen formation. To see how quickly a change in orders is made, and differently, just cut a section of stem into a cutting and plant it. The new cells now have orders to form a healing callus and roots, not stem tissue.

We know that the complete DNA message has gotten through to the new cells because later one of these new roots may send up a sprout which, even though it came from root tissue, got the change order to make stems and flowers. How was the change order given and how could it be converted back?

Dr. James Bonner, biologist, at California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, discovered that a kind of protein called histone, always found in the nucleus of cells, plays a major part in deciding what that cell will become. Since the DNA in the cell nucleus acts as a kind of master tape (or a punch card) for all kinds of cells in an organism how does the cell know what part of the message to read?

Dr. Bonner and his associates, by microscopic studies, found that some of the DNA was wrapped in histone and that the DNA thus wrapped could not make copie's of itself, called RNA (Ribonucleic Acid) , to start differential cell growth. Histone obscured part of the blueprint, and thus the cell could follow only those instructions not wrapped in histone. It is something like the flutist or the clarinet player in the orchestra. The complete instrument is there but only the notes are played which are not covered.

What does all this have to do with miniature roses? Really, this is the explanation we have needed to help us see what is happening. As I have long suspected the determining factor in miniatures is probably not a dominant gene or genes. It is more likely a blotting out or covering up of certain portions of the basic rose "message." Instead of behaving like a normal rose in all of its areas only part of the orders may be getting through. Thus, instead of a full size rose such as a normal China or hybrid tea, a compromise has to be made. As far as the rose is concerned this may not be good because along with this miniature size is linked the loss or diminution of fertility.

This does not imply, however, that the loss of fertility makes miniature roses any less desirable for use in our homes and gardens. They have been bred for this purpose and man has only taken advantage of a freak of nature. These plants would be at a decided disadvantage in nature; even under the most ideal growing conditions they would be unable to effectively reproduce by sexual means (seeds) . Miniature roses must depend almost entirely upon the skill of gardeners and nurserymen for continued existence.

Perhaps this phenomenon of the miniature rose is not just a one time performance. It may not be an indelible change in the gene or DNA (master tape) and may be repeatable whenever the complete message (blueprint) is inhibited or blocked in this certain area by the histone covering. Certainly as shown in the experiments recounted earlier, this would appear to be true. This particular, or very similar, "mutation" may apparently be picked up in roses having quite different backgrounds. Since they can be made to "breed true" to such extent that a whole race of miniature roses has resulted, might not many other so-called mutations originate in the same way?

In such case they would not only be repeatable but they could also be reversible (that is revert to original type) whenever the blocking of the full message was removed. This would imply that the portion of the "message" blocked by the histone covering is still blocked in succeeding generations either by this covering or other inhibitor (s) . It is not likely that this is an extra-chromosomal gene since, as pointed out, I have used miniatures as the pollen (male) parent in nearly all cases. Experiments have shown that extra-chromosomal genes are transmitted only from the female parent (but there still are unknowns in this area) . For more information on this subject see "Genes Outside the Chromosomes," Scientific American, January, 1965, pp. 71-79. In this respect these mutations should be considered as temporary changes or adjustments. In nearly all cases they Would be inferior at some point to the original insofar as structure, function, stability and reproduction of the species is concerned. No matter how valuable, beautiful, or useful these variants might be considered by our society, they may not be permanent.

Other factors may also be at work, either individually or collectively, to cause changes or present problems. It has been discovered that certain abnormalities may be due to chromosomal disease. Whether or how this may be of any present importance to miniature roses is not known.

The major troubles (disease and insects) which may cause any appreciable damage or concern, insofar as miniatures are concerned, have been covered earlier. However, one other trouble which at times may give considerable concern is crown gall. Some areas seem to be relatively free of this problem but it is a malady of major concern to commercial growers of roses, fruit and certain kinds of shade trees.

The crown gall disease is a kind of plant cancer or tumor. Laboratory experiments have shown that crown gall disease is caused by a tumor-inducing principle produced by infection of the plant with a certain soil-borne bacterium.

Normal cells are transformed to tumorous cells only when the plant has been wounded or damaged, allowing entry of the bacterium involved-even cutting or bruising in the normal process of making a cutting. It has been noted that cells (tobacco plants) which are transformed to tumorous cells in the period between 60 to 72 hours after wounding are most malignant. Those which are transformed earlier are less so. (For further information, see article: "The Reversal of Tumor Growth," Scientific American, November, 1965.)

My observations along this line deal more with prevention than cure. Sanitation in the nursery is important. Dipping all tools, knives, shears (and cuttings before planting) in a Clorox solution has been found effective.

But it appears to me that the variety has much to do with resistance or susceptibility to infection. We have grown more than a million plants (cuttings) of a certain red miniature and to date no more than six plants have shown any indication of crown gall.

These plants were handled bare root so there was ample opportunity to observe. Even these few were so slight that we are not sure that it was not just a heavy callus. Others of similar heredity seem to also have this marked resistance to crown gall.

Still other seedlings having the same mother parent as the variety above but different pollen parent (s) have shown marked susceptibility to crown gall. Thus whenever we tried crosses involving the variety 'Masquerade' (floribunda) or 'Alain' (floribunda) on our mother parent (0-47-19) we got a very high percentage of crown gall among the seedlings. 'Alain' seems to pass this susceptibility down to the miniatures even in succeeding generations. It was noted that whenever a certain red climbing miniature seedling was used as the pollen parent on 0-47-10 as seed parent, the offspring (some very nice looking miniatures) would develop heavy crown gall. This red climber was one-half 'Alain.' The variety 'Cricri' also shows considerable tendency to crown gall. Its parents are ('Alain' X 'Independence') X 'Perla de Alcanada.'

If we can weed out and eliminate potential trouble makers from our breeding we have made a giant step toward developing better varieties. So We should not think that time and money spent in furthering this end is lost or wasted. We may be forced to test other potential varieties in the search for better and still better breeding materials. This is all part of the challenge. The goal is as always-to combine the best parents for the purpose, to use varieties offering the most good or desirable qualities and the fewest undesirable.

Return to Table of Contents

Back to Old Garden Roses and Beyond