|

|

Albas |

The following appreciation of J. P. Vibert is written by Brent Dickerson, whose web site can be viewed at: http://www.csulb.edu/~odinthor

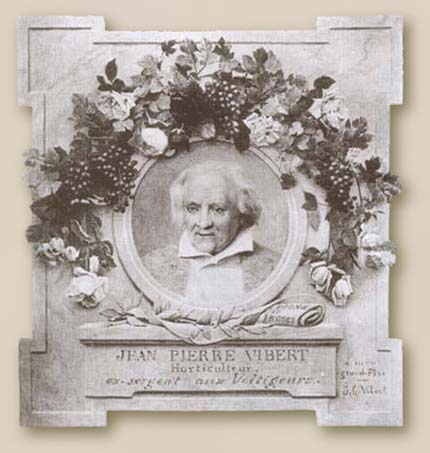

Vibert was born on January 31, 1777, in Paris, France. He was age 12 when the Bastille fell, 15 when Louis XVI was guillotined, 17 during the Reign of Terror. Perhaps he was eye-witness to some or all of these events! One certain thing is that he joined Napoléon's First Army of the Republic; and, as a result of his wounds sustained at the Siege of Naples, returned to Paris, where he set up as a hardware shop owner. His shop was near where Dupont, one of the Empress Joséphine's favored rose suppliers and researchers, had his rosarium. This proximity fostered Vibert's interest in roses and rose-breeding. The Napoleonic Wars ended with the British troops over-running Paris. Descemet, perhaps the earliest European practitioner of controlled cross-breeding in roses, had to flee the country for political reasons; the French government failing to indemnify Descemet for the losses he sustained due to the invasion, Vibert bought out what remained of Descemet's premises and properties, including, in particular, remnants of his breeding-notes, and his roses—both the nursery stock and his seedling new cultivars. As he prepared the release of his own first cultivars (to take place in 1816) as well as those from Descemet's last crops, he was struck with, first, the death of one of his daughters in 1815, then, in early 1816, the death of his wife. Recovering from these blows, he nursed his business into prosperity. Along with his rose-breeding and selling, he began to publish enlightened essays and articles on roses in the 1820's. But, with Fame comes a price to be paid. In one of his essays, Vibert inadvertantly wounded the self-esteem of one of the "in"-crowd of the court, and had to spend the latter half of the 1820's defending himself—brilliantly and courageously—against the sneering, partisan attacks of members of the court's horticultural clique, comprised for the most part of pompous professors, botanists, artists, writers, journalists, and nurserymen mostly forgotten today. It should not be underestimated what Vibert put at risk in doing this! Disfavor from the insiders at the court would have a chilling effect on business. Despite this—or perhaps because of his skill in dealing with it—his affairs flourished, and he became one of the most respected rosarians and nurserymen in the area of Paris. He indeed became a founding member of the Société d'Horticulture de Paris, which at length became today's Société Nationale d'Horticulture. His penchant for speaking out against horticultural abuses of the gardening public again embroiled him in controversy in the 1830s and 1840s when he pointed out in print repeatedly the failure rate of the "forced grafts" which Parisian nurserymen, in particular, were putting on the market. He bred with, and offered, roses of all sorts, from the new Chinas and Teas (he was the first to introduce to French horticulture the first yellow Tea, 'Parks' Yellow Tea-Scented China', so important to later breeding in France), to Noisettes (he bred the still-popular 'Aimée Vibert'), to the traditional Albas, Gallicas, Centifolias, Mosses, and Damasks, remaining a large-scale breeder of these several traditional classes long after public interest in them had diminished. He had a particular interest in Damask Perpetuals, and also bred some early Hybrid Perpetuals. He delighted in striped and spotted roses, and bred many such among the Gallicas, Centifolias, etc. Many, many of the roses still being sold in these groups were originated by Vibert; a check of the catalog lists of today will find Vibert's name omnipresent. Even this was not enough for the ambitious spirit of Vibert. He also became interested in breeding raisin-grapes!—and offered many new hybrids of his own, writing about his results and experiences in the journals of the time. Further, he was unceasing in his search for good, new, roses, and pursued much travel with this in mind, becoming known in particular to the most respected English nurserymen such as William Paul and Thomas Rivers. Many roses which otherwise would have remained unknown in the gardens of home-breeders or in the nurseries in other countries were distributed far and wide by Vibert, whose business connections spanned Europe from north to south, and across the sea to America as well. At length, after a brilliant and honorable career, in 1851, at the age of 74, he retired, a successful businessman, to the environs of Paris, spending his latter years still writing letters and articles to the journals of the time, and no doubt devoting his time to his own garden. He sold his business to his nursery foreman, and the business continued into the 1890's, Vibert's breeding lines being continued by his successors. Finally, as his grandson, the successful and popular artist Jehan Georges Vibert reported, "Some days before his death, while arranging his daily bouquet in a vase, he said to his grandson: 'See, my child, a man knows truly what he has loved best on earth only when in his last days he finds it still in his heart. Like the rest of the world, I have thought that I adored and detested many men and many things. In reality, I have loved only Napoléon and roses. Today, after nearly a century of rebellion against all the evils which I have suffered, there remain to me only two objects of profound hatred: the English, who overthrew my idol, and the white worms that have destroyed my roses'." Soon after, on January 27, 1866, four days before his 89th birthday, he died quietly during the night at home. As a contemporary wrote, "We should wreathe his tomb with our homage and our respect." The roses which he bred, and those from others which he popularized and sold; his practices and his skill; his articles and his opinions—all of these influence the roses of today in a way which no other rosarian in rose history could claim. But, at length, it is his culture and familiarity with literature and history, his sense of the beautiful, his striving after the previously-unattained, his belief in straightforwardness and honesty, and his grasp of principles both botanical and societal—in short, his goals, his knowledge, and his ethics—which leave one with such admiration for the man. With him, as with few others, we feel that here is a man who has endured the challenges of Life, has had the highest aspirations, and has triumphed on his own terms. (The illustration above of Jean-Pierre Vibert, the only known representation of him, is by his grandson Jehan Georges Vibert; but, to know him truly, to know his heart, we must know his roses.)

Original photographs and site content © Paul Barden 1996-2003 |

|

Jean-Pierre

Vibert, the master rose-hybridizer of the first half of the 19th Century,

introducing hundreds of roses from 1816 to 1851, man of strong opinions,

courage, and discernment; enlightened, skilful author; soldier under

Napoléon! No one can study rose history or old roses without being surrounded

by the name Vibert; no one can grow roses old or new without feeling

his often silent influence. And yet, so modest was he about himself

personally that all details of his life—even including what his first

name was!—were completely unknown until I, assisted overseas by a French

colleague, had the good fortune to be able to discover this personal

data buried in French civic records and scattered as stray remarks in

periodicals contemporary with Vibert. In homage, then, to this commanding

figure in rosedom, I offer this home page, consisting of a few short

notes on a man deserving volumes.

Jean-Pierre

Vibert, the master rose-hybridizer of the first half of the 19th Century,

introducing hundreds of roses from 1816 to 1851, man of strong opinions,

courage, and discernment; enlightened, skilful author; soldier under

Napoléon! No one can study rose history or old roses without being surrounded

by the name Vibert; no one can grow roses old or new without feeling

his often silent influence. And yet, so modest was he about himself

personally that all details of his life—even including what his first

name was!—were completely unknown until I, assisted overseas by a French

colleague, had the good fortune to be able to discover this personal

data buried in French civic records and scattered as stray remarks in

periodicals contemporary with Vibert. In homage, then, to this commanding

figure in rosedom, I offer this home page, consisting of a few short

notes on a man deserving volumes.