|

|

Albas |

Padre

of the Roses The

good he scorn'd

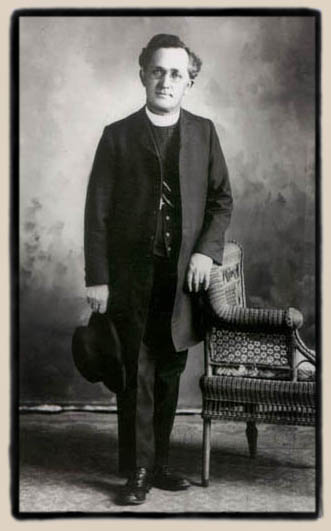

George Schoener was born in Steinbach, Baden, Germany, on March 21, 1864, and died in Santa Clara, California, on October 2, 1941. It is the final irony of an extraordinary life that his tombstone in Calvary Cemetery, Santa Barbara, has the year of his birth as 1862. He never lost the conviction that he was the underdog, maligned because of his religion and unorthodox horticultural ideas. But widespread misunderstanding about him was, in part at least, the result of his own dissembling. Why he lied and deflected questions about his place of birth remains a mystery, but anti-German feeling during the first World War and his humble peasant background may explain it. At right: A studio portrait of Father George Schoener during his Oregon years. Photographs from the Schoener collection courtesy of the University of Santa Clara Archives The documents of Schoener's life, buried in the archives at the University of Santa Clara since his death, reveal a little of the activities and complex character of this tortured man. Schoener's letters, articles, and journals and references to him by others suggest a fractured life of striving and frustration; a personality divided between humility and arrogance, charity and acquisitiveness; an immigrant who became a Catholic priest, served the church among other immigrants in Pennsylvania, and collapsed from overwork, eventually contracting tuberculosis; editor of a liturgical art magazine; writer whose plays were never produced, whose novel was rejected by Alfred Knopf, and whose manuscript 'Guide Into the Catholic Church' and execrable verse were deemed unsuitable for publication.

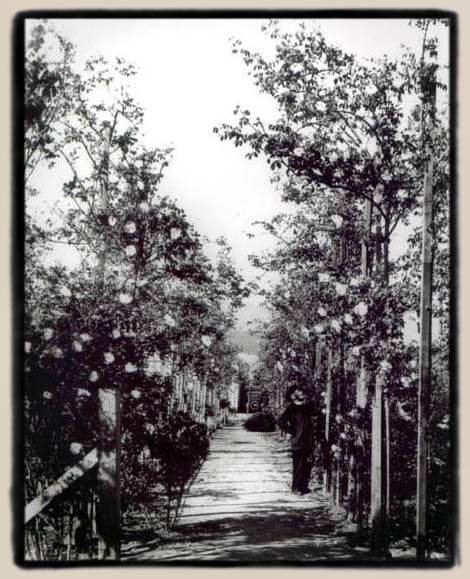

He was unwavering and forthright in his politics, and recognized Adolph Hitler as the power-hungry maniac he proved to be. For Schoener, Hitler and the anti-Semite Father Couglin, whose outrageous commentaries broadcast over radio and in the press were remarkably popular in his day, were cut from the same cloth. In breeding roses, Schoener not only used the hybrids raised by others, but also incorporated the germplasm of wild roses-a method beneficial in increasing the probability of disease resistance in hybrid plants, but one less likely to produce quickly marketable results. He stimulated interest in the unconventional and encouraged others to question traditional methods of breeding plants. His essays and letters aroused discussion. Years after his death a square in his home town was named for him. At left: La Avenida de las Rosas, Milpas Street, Santa Barbara: Schoener's rose trees, said to be thirty feet high, were photographed near the end of the flowering season As a priest he struggled to reconcile his ambition and search for fame with his vocation. Assigned to a missionary church in rural Oregon, he chafed at the lack of intellectual stimulation, but found joy in the creation of new plants. Just as he was becoming established as a rosarian of note, the church and library his house and greenhouses full of seedlings burned to the ground. Offered a new place in Portland for his work, things went awry again, and two years later he moved to Santa Barbara. Santa Barbara was the ideal place for a horticulturist. The balmy climate and increasing interest in gardens among wealthy residents provided an atmosphere conducive to experimentation with a wide range of plants. Francesco Franceschi and Joseph Sexton had shown the way, and Schoener bought a house and grounds and established a nursery there.

It seems probable that the move was engineered for botanical rather than clerical reasons; his correspondence conveys that impression when read between the lines. He became a familiar figure among winter visitors on vacation, and was heard from frequently in the press. These were the years of his best work in the garden and outside it. He earned the informal title Padre of the Roses, relished it, and had it printed on his stationery and in his catalogs. But in 1939 his health began to fail and he overreached himself financially He had to sell out, and was keenly disappointed when plants offered to the Huntington and other botanical gardens were declined. He moved to Santa Clara and tried to establish a new garden and nursery at the Jesuit university there, but it came to nothing. He died two years after moving to the town. During his four years in Brooks, Oregon, he had searched the countryside for the native Rosa nutkana and R. gymnocarpa and some of the wild roses that had invaded the area, which he used in his crosses to create hardy, disease resistant garden shrubs. He asked for help with seeds and information from hybridizers and noted rosarians such as Ellen Willmott in England, Wilhelm Kordes in Germany, and Alex Dickson in Ireland, as well as staff at several botanical gardens throughout the world. All traces of his house and nursery in Brooks have vanished. A few unidentified roses that may have been his dot the ravines and hillsides around the town, and these have been propagated and await identification. Perhaps some will be among the forty-three roses connected with Schoener mentioned in old newspapers, award notices, and correspondence.

The Santa Barbara years saw many attempts to raise money for his work on roses. He took every opportunity to use the press and radio for his cause. He named a dark rose, described as black, for Oliver Wendell Holmes, who sent money for his research. Throughout these years his cousin, Anna Schmitt, helped him financially, defended him against detractors, and acted as his housekeeper and cook. At left: 'Pearl of the Pacific' (1919), a hybrid tea rose raised by Schoener pictured five days after a show. The rose is now lost. His greatest success came with Rosa nutkana, when he was able to cross it with 'Paul Neyron', a hybrid perpetual rose with large, fragrant, liac-pink flowers raised in 1869. R. nutkana is a large shrub with gray-green leaves and single pink flowers that tolerates poor soil and shade. The combination of these plants produced a vigorous shrub with fine attributes from both parents and the additional benefits of few thorns and lovely perfume. Called 'Schoener's Nutkana', it was released by Conard Pyle in 1930 and has found its way into gardens and nurseries around the world. The other rose

raised by Schoener that perpetuates his memory is 'Arrillaga', introduced

by Bobbink and Atkins in 1929 and occasionally listed in catalogs today.

It is a hybrid perpetual descended from, among others, 'Mrs John Laing',

'Frau Karl Druschki', and Rosa centifolia. The flowers, strongly

scented and carried on long stems, are large, double, and vivid pink

with a golden base. In my garden it flowers At right:"Schoener's Nutkana" (R. nutkana X Paul Neyron), 1930. As a young man,

Schoener was described as having keen blue eyes, erect and sturdy physique,

and a light and springy step. In the Santa Barbara years he was an "old

gentleman in rather soiled clerical dress walking along Milpas Street

to and from his garden.' But his steely persistence and bold concepts

are worthy of emulation by those contemplating careers in rose hybridizing.

His was a period of intense interest and activity among hybrid tea rose

breeders, and research funds went almost exclusively to the development

of these reblooming plants. Today, renegades like Schoener find encouragement

among the many gardeners ready to embrace unusual plants; in this more

adventurous climate, had he been able to develop fruitful relationships,

he might have found both emotional and financial support and flourished...?

At left: the Hybrid Perpetual 'Arrilaga', introduced in 1929. This rose is still in commerce in 2000. My thanks to Bill Grant for allowing me to reproduce this article here, and to the Santa Clara University archives, and to Pacific Horticulture, which published the origional article. Thanks to all! A document by George Schoener, and others, on Breeding With Rosa gigantea. This article copyright © William Grant, 1999-2000.

There

have been |

|

The

public knew him as Padre of the Roses; editors knew him as a tireless

letter writer who complained, corrected, and pleaded; nurserymen and

botanists around the world tired of his importunity; bishops shipped

him off to other dioceses; and he covered his tracks so well that most

believed him a native of the United States.

The

public knew him as Padre of the Roses; editors knew him as a tireless

letter writer who complained, corrected, and pleaded; nurserymen and

botanists around the world tired of his importunity; bishops shipped

him off to other dioceses; and he covered his tracks so well that most

believed him a native of the United States.

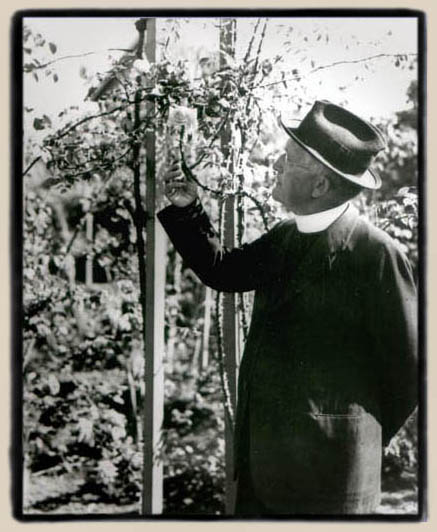

At

right: In this newspaper photograph Schoener was described as the Padre

of the Roses and is shown with a new rose, a descendant of Rosa gigantea

and 'Souvenir de Claudius Pernet' and his first with non-fading yellow

flowers.

At

right: In this newspaper photograph Schoener was described as the Padre

of the Roses and is shown with a new rose, a descendant of Rosa gigantea

and 'Souvenir de Claudius Pernet' and his first with non-fading yellow

flowers. While

in Santa Barbara he experimented with

While

in Santa Barbara he experimented with  intermittently

all summer, but in less benign climates it is restricted to one flush

of bloom. In 1935 Schoener was given a special award at the Bagatelle,

Paris, annual competitions for 'Glory of California', a vigorous yellow-flowered

climber, presumably now lost to us. Some were led to believe that he

had gone to Paris to receive the award and deliver a lecture. He won

certificates for his roses at other shows, too, and was judge at the

annual rose festival in Portland , Oregon. He worked also with vegetables

and fruit, but little is known of his success with them.

intermittently

all summer, but in less benign climates it is restricted to one flush

of bloom. In 1935 Schoener was given a special award at the Bagatelle,

Paris, annual competitions for 'Glory of California', a vigorous yellow-flowered

climber, presumably now lost to us. Some were led to believe that he

had gone to Paris to receive the award and deliver a lecture. He won

certificates for his roses at other shows, too, and was judge at the

annual rose festival in Portland , Oregon. He worked also with vegetables

and fruit, but little is known of his success with them.