|

|

Albas |

Welcome to the January 2003 edition of my web site! The roses I write about are the Old Garden Roses and select shrub and miniature roses of the 20th century. For tips on rose culture, pruning, propagation and history, see the "Site Resources Guide" box in the navigation panel at left. To return to this page, click on the "thorn icon" in the margin at left. Articles from the previous months are archived and can be viewed by clicking on the listings in the left margin. Oh, and please don't write to me for a catalog or pricelist.....this is an information site only, not a commercial nursery. If you wish to buy roses, see my sponsor, The Uncommon Rose. Climbers:

If It's Taller Than A Bush, What Do I Do With It?

I currently grow four climbing roses plus several hybrid teas that think they're climbers. Over the past four years since I began growing "super-sized" versions of my favorite plant, I have read everything I could get my hands on about the care of climbing roses. Unfortunately, most of the information I have come across has been sketchy at best, and sometimes it doesn't make a lot of sense. Since I am frequently asked how to care for climbers, I would like to offer some thoughts for your consideration. This article is a synthesis of studying what the experts have written combined with my own experiences and tempered by numerous discussions with other rosarians.

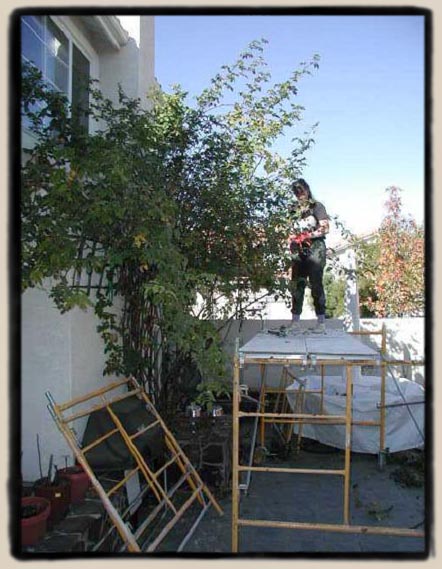

For the purposes of this article, I would like to put any bigger-than-a-bush rose into the loose definition of "climber". The reason is that many of the same ideas that I talk about work similarly on the taller English roses, as well as the monster hybrid teas such as 'Folklore' and 'Maid of Honour'. Extra tall roses can be trained as climbers or pillar roses; just because a rose isn't identified as a true "climber" doesn't mean that it doesn't exhibit the characteristics of one. The "problem" of overly vigorous roses seems to be especially prevalent here in Southern California: Clair Martin's 100 English Roses For The American Garden addresses the phenomenon with respect to the roses hybridized "across the pond" by David Austin, but English roses are by no means the only ones that insist on growing way over our heads. Treating such roses as climbers can bring an added dimension to enjoying their charms. Let's begin by saying that climbing roses are cared for somewhat differently than their smaller siblings. The basics-water, sun, fertilizer, etc.-are essentially the same (although in proportionally increased amounts), but it's the pruning and shaping that are different than "regular" roses. While those differences can cause some anxiety at first, much of the mystery of maintaining a climber will fade once you start understanding some climber characteristics. Your first clue in knowing how to care for your climber is its nametag. Knowing the name of your rose will allow you to research its traits. If the nametag is long gone, then careful observation will do almost as well. Figure 2: This is why I can't deadhead throughout the year. A ladder is too short, and the only thing stable-and tall-enough is to rent a scaffold, which can get expensive.

To tie the canes, you can use any strong, stretchy, flexible material. Plastic non-stick garden tape works well, as do old pantyhose. You don't want to use something that doesn't give because it can girdle a cane as it grows; and once girdled, the cane will die above that point. Note: If you affix a trellis to a house or other rigid structure, resist the temptation to thread the baby canes between the trellis and the wall. As the young canes grow, they will force the trellis away from the wall, and can tear a trellis apart. Always tie a cane to the trellis. For all intents and purposes, there are two types of climbing roses: those that bloom once a year, and those that are repeat-bloomers. A once-blooming rose is normally pruned after it finishes blooming, while a remontant rose is pruned as it goes dormant. Plan to prune repeat-blooming climbers when you prune your other roses.

Once-bloomers are gearing up for their flush as they come out of dormancy. Therefore, if you prune a once-bloomer in the spring, you have just removed its flowers for the year. Wait until after it has finished blooming, and then reduce the laterals by about a third, remove all dead and spindly growth, strip off and discard the leaves to reduce the spread of disease (now is the time to dormant spray against pests and fungi), and shape the plant to your preference. "Shaping" can involve pruning, training, etc.-whatever is needed to make it grow more or less in the shape you desire. For example, half of my climbing hybrid tea 'Paradise' is trained to grow up my chimney, and the other half grows horizontally under my bedroom window on the second story of my house. Determine if the plant blooms on old wood, new wood, or a combination of both. (Again, knowing the name of the rose will go a long way in helping you understand its idiosyncrasies.) "Old wood" is growth that was produced last season, while "new wood" is from the current year. Climbers have very definite preferences, so if you buy a bareroot climber that only blooms on old wood, be prepared to wait a whole year before you see its first bloom. Climbers that repeat-bloom are pruned and shaped in much the same way as once-bloomers, except that the pruning is performed at dormancy (the "normal" time for pruning roses). Keep in mind whether the climber blooms on old wood or new wood, so that you don't take off too much of the wrong kind and inadvertently cause a poor showing in the coming season. To encourage a better repeat-bloom throughout the year, keep spent flowers deadheaded, which can be a daunting task when your climber is over 20' tall! When do you get rid of main canes? Very old canes will gradually produce fewer and fewer flowers, so remove these canes once the rose has produced new basal growth to take their places. Main canes will be viable for several years, so don't stress about "having" to remove some each season. See? Climbers aren't so difficult to understand after all! Copyright © Anastasia Shupp 2003 For yet another look at pruning techniques, here is Don Julien on the "Scarman Method" for pruning OGR's. You may also want to take a look at Kenneth Grapes British study on an alternative pruning method being studied by the RNRS.

There

have been |

|

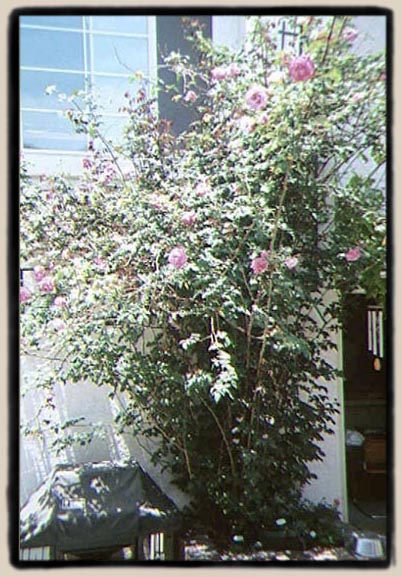

Figure

1: Remontant climbing hybrid tea, 'Paradise', planted bareroot

in 1997. It only blooms on old wood, and I think it produces just one

main flush because it's too tall for me to deadhead!

Figure

1: Remontant climbing hybrid tea, 'Paradise', planted bareroot

in 1997. It only blooms on old wood, and I think it produces just one

main flush because it's too tall for me to deadhead!  Most

climbers are comprised of long main canes that sprout secondary, or

"lateral", canes. It's from these laterals that the majority of flowers

bloom. Each cane contains a hormone that tells the cane to bloom. This

hormone naturally flows to the highest point on the cane, which is why

a cane that points straight up usually has a flower or cluster of flowers

at its tip while the rest of the cane just produces leaves. To encourage

a cane to sprout more laterals and, therefore, more flowers, gently

train the canes as horizontally as possible. This distributes the hormone

along a much greater area. "Self-pegging"-tying long supple canes down

to the ground or to the base of the plant-is another method that redistributes

the blooming hormone, and has the added benefit of creating a very different

look in your garden.

Most

climbers are comprised of long main canes that sprout secondary, or

"lateral", canes. It's from these laterals that the majority of flowers

bloom. Each cane contains a hormone that tells the cane to bloom. This

hormone naturally flows to the highest point on the cane, which is why

a cane that points straight up usually has a flower or cluster of flowers

at its tip while the rest of the cane just produces leaves. To encourage

a cane to sprout more laterals and, therefore, more flowers, gently

train the canes as horizontally as possible. This distributes the hormone

along a much greater area. "Self-pegging"-tying long supple canes down

to the ground or to the base of the plant-is another method that redistributes

the blooming hormone, and has the added benefit of creating a very different

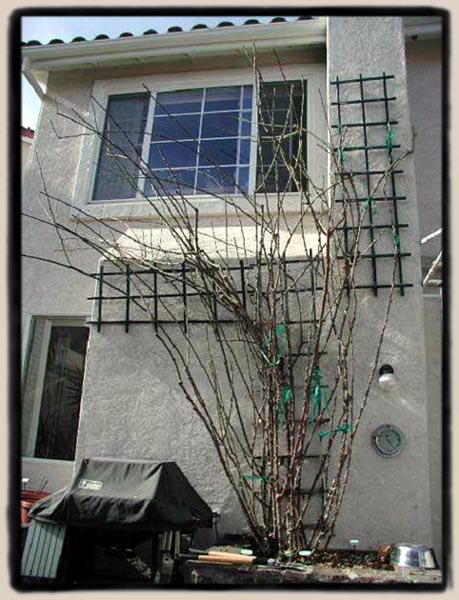

look in your garden.  Figure

3: Dormant pruning is complete. It took me 4-1/2 hours, but

all dead and spindly growth is gone, the laterals have been reduced,

and the canes have been re-tied to shape the climber as desired.

Figure

3: Dormant pruning is complete. It took me 4-1/2 hours, but

all dead and spindly growth is gone, the laterals have been reduced,

and the canes have been re-tied to shape the climber as desired.