|

|

Albas |

Welcome to the December edition of my web site. The roses I write about are the Old Garden Roses and select shrub and miniature roses of the 20th century. For tips on rose culture, pruning, propagation and history, see "Other resources on this site". To return to this page, click on the "thorn icon" in the margin at left. Articles from the previous months are archived and can be viewed by clicking on the listings in the left margin. Oh, and please don't write to me for a catalog or pricelist.....this is an information site only.....not a commercial nursery. If you wish to buy roses, see my sponsor, The Uncommon Rose. Thanks! This month I have chosen to reprint Leonie Bell's wonderfully detailed article on the mystery Shrub Rose, 'Banshee'. I get one or two requests to identify this rose every year, so it seems that people encounter this rose all over the continent. (My plant was given to me by a friend in Hamilton, Ontario several years ago, long before I knew what this rose was!) 'Banshee' is sometimes confused with 'Maiden's Blush' or others of the Alba clan, but it is unique enough to be recognized as distinct from these. The bloom has Alba-like qualities, but that is where the similarities end! As you will see from my photographs, the clone I have is absolutely identical to the plant that Mrs. Bell so skillfully illustrated here. I hope that this article will help some of you to identify that "mysterious stranger" in your garden! Banshee: The

Great Impersonator

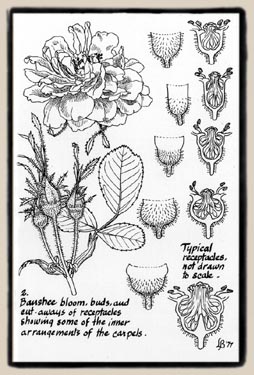

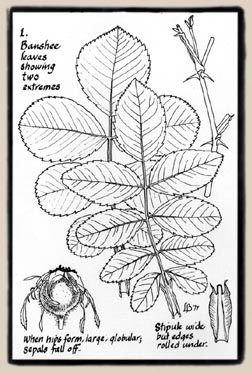

Click on the image to see a larger, more detailed version. Once you have learned to recognize the outline of typical leaves, you may wonder how you ever mistook this rose plant for any other. Yet confusion as to the name and class has haunted it quite as much as balling. Our most knowledgeable rosarians, Americans as well as English, have been hoodwinked by this rose, mainly, I think, because they see only the color of the bloom and do not look below the bud. In identification, flower color alone is not enough to go by, any more than a given name is. What can be neither questioned nor overlooked is the marvelous perfume of the opened blooms, the quality that first drew me into the spell of the Banshee Rose. I did not experience the rose first, then wonder what it could be. Quite the reverse. A name and description appeared in Edward Bunyan's Old Garden Roses of 1936. At the end of his book, that has become a classic in the rose world, there were some leftover kinds that defied classification but were too good to leave out. Here I found: Banshee. Double, palest pink, deepening to centre, 2 and 1/2 inches. Numerous stamens mixed with petals. Very penetrating scent, like Lucida. Hip acorn-cup shaped. Calyx more than twice length of bud, densely glanded, wings over 1/2 inch long, narrow, often dividing. Leaves strong green, large for size of flower, smooth, thornless, petiole channeled like a Tea. Stipules long, broad, serrate, edges waved. This was sent to me from Canada under this name as the hardiest Rose grown there. I have not so far been able to identify it. It is remarkable for the penetrating Eau de Cologne scent, and will delight all lovers of scented Roses, being sui generis in this.

(Even such a loving description needs a bit of explanation. "Acorn-cup

shaped" is a simile more accurate than some thought up earlier, as you

shall see. Bunyard's "wings" are the pinnules or foliations present

along the edges of the sepals. By "sui generis" he meant, of

course, unique, one of a kind, or all its own, a reference to degree

of fragrance rather than to type. "Petiole channeled like a Tea" is

irrelevant because all rose petioles are channeled to an extent.) From the moment that information sank in, I knew I was on a collision course with a very special rose. The clues came slowly at first. The library of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, nearby in Philadelphia, has a complete run of the Annuals; I borrowed a few at a time, starved for rose lore. A relative was about to throw out several years of HORTICULTURE when that magazine was a twice-a-month tabloid chock full of low key plant news and fascinating exchanges of letters from the horticultural deities of the time. I took the lot. In the 1940 American Rose Annual, Percy Wright gave a Canadian's viewpoint: One of the commonest rose varieties grown in western Canada is the Banshee. It came into the country so long ago that its origin is forgotten, and inquiry only elicits the opinion that it reached Manitoba via the Dakotas, and from the Red River settlements was carried into Saskatchewan and Alberta. It may be `an old rose', and yet the foliage seems distinct from that of Gallica and Centifolia. The flower is a very double pink of poor texture, not unattractive, but much troubled by balling. Hence, I suppose the variety name . . . This year a bud sport gave a new form, a semidouble rose of much deeper pink and free of balling, and with the loss of petals, fertility was recovered. As soon as 1 found this plant I attempted to use it in crossing, and placed upon its petals pollen of a wild rose that happened to be in bloom at the same time. This was [here lie continues in HORTICULTURE, February 1951 ] Rosa lucida or virginiana, the plants of which came from [Kentville] Nova Scotia and were a very hardy form. Every pollination gave seed, and the idea was suggested to me that perhaps Banshee itself is a hybrid of this or some related North American native. Much was to be learned from Mr. Wright's experience. The strange name derived from the fact that many buds failed to open; this notorious fault was due to the degree of doubleness and not to unseasonal weather; the plant was capable of sporting both as to petal number and petal color, and therefore might exist in other forms (for instance, Bunyard's version must not have balled); when semidouble it was fertile with a native species having 28 chromosomes, and if this species were Virginiana (for which R. lucida is synonymous and now obsolete), then the extreme hardiness, scent, and proclivity to sucker would be explained. Do not think that all this hit me in one flash! Hardly. Mr. Wright then told how he'd tried to incorporate Banshee into his breeding program, without success, for when at all double, the offspring invariably balled. He and his mentor, Dr. F. L. Skinner, were as curious about its identity as you and I are: There has been a good deal of speculation about what the right name of the Banshee rose is, for obviously it has been renamed right in the "blizzard country" where it has proved best adapted. A letter received just today from a rose correspondent in New York . . . suggests it is none other than the famous old "Maiden's Blush" : This suggestion has been made before but Mr. Skinner [this, in 1951 ] at once denied its validity. The flower of the Maiden's Blush rose is better than the flower of Banshee, and was not troubled by balling in my climate, but the plant was so much less hardy than Banshee that they all died out within a year or two.During the summer of 1947, Mr. Skinner took a trip to northern Europe, visiting Sweden among other countries. While there, he noticed the Banshee rose growing in a botanical garden under the name of Rosa amoena grandiflora. "Amoena" translates to charming while "grandiflora" means large-flowered, both but a garden name, botanically a deadend.

That same spring, when three more arrived from the Hudson Valley, New York, each called Banshee but with extra descriptive words to indicate slight differences, their new leaves left no doubt that they and the North Dakotans were identical. As the Crosby pair sent out first the fresh green leaves, smooth, with wedgeshaped bases, then tight clusters of buds preceded by unbelievably long sepals, I wondered why no one had written how beautiful they were. Finally, as each kind showed color, I held my breath, so to speak: they did not ball! Yes, the scent was very nice though would not be fully appreciated until a year or two later. And marvel of marvels, the less double set quite a few round dull red hips.

These two were set safely within the confines of an old masonry coldframe.

The three New Yorkers, planted optimistically beyond the garden proper

where they might sucker as they would, were gradually cut to oblivion

by the mowers in this family. No matter; I sensed more would come my

way and they did. Click

on the image to see a larger, more detailed version. Now other writings began to make sense. Professor Stephen Hamblin's description, for example, of his supposed pink Alba in the 1943 American Rose Annual: Almost equally abundant [as Alba Flore Pleno] and spreading rapidly by its own root system, is what is called Maiden's Blush. This stands five feet tall, in great tangles, the leaves very smooth and very pale green. No plant has foliage quite like this one. The flowers are large, very pointed in bud, very double, blush pink, but often so double that they do not open well for the outer petals turn brown and hold the flower closed. The pale green (pea green) foliage and blighted buds are the identity mark of this rose which can be in any old garden, a companion to the Apothecary's Rose but much taller as a plant. It is offered to you by gentle souls as a "Damask"; a "Cabbage"; or some rarity from an aged aunt, but it is but Maiden's Blush. From a Canadian dealer in old roses it came to me as `Banshee'; noted for its blighted flowers. The records credit this rose to Kew Gardens (1797) and it must have been planted in New England gardens the following year. It is thought to be a hybrid of the York or Cottage Rose [Rosa alba] but it is very different . . . and may be rated botanically as R. alba incarnata or R. albs rubicunda . . . I like his phrase "pea green"; the leaves are about the color of cream of split pea soup. The rose that is credited to Kew Gardens in 1797 is not Banshee, by whatever name, but the true Alba `Maiden's Blush'. Why did he not recognize the Canadian rose as being different from the true Albas? Did he not know there was a true pink Alba? Perhaps he thought this was a contradiction in terms. In her book of 1935, Old Roses, Mrs. Keays, who must have been in close correspondence with Prof. Hamblin, expressed thanks to him for his gift of Alba Flore Pleno, "which set us right with the Alba roses from the beginning." She described her two pink "Albas", "Clustering Maiden's Blush" and "Celestial", then dropped the subject abruptly, only to resume her uneasiness about Albas in the Annuals of 1937 and 1941: Clustering Maiden's Blush is an Alba which we have found repeatedly around old cabins and in the oldest neighboring gardens. It has the fascination of a delicate color and texture which its name expresses, Foliage is less blue than the type; the calyx is round and blunt like a thimble. The long sepals tapering to a slim point are sometimes spatulate, but not so decorative as the more fern-like sepals of the type Albas. She also adopted Prof. Hamblin's terminology for her oddly different pink roses and called attention again to the unusual receptacle or calyx-tube: The turbinate calyx occurs in another rose much more widely spread [than R. francofurtana] -the Alba, var. Rubicunda, where lies the ancient Maiden's Blush. In this group the blue-green of Alba gives way and the foliage is pale and not positively blue . . . The Maiden's Blush roses have a blunt calyx-tube, like a thimble . . . The pink Alba is delicately green, at this time taking on a lovely autumn salmon color. The bush is lady-like, pastellish; neat and clean . . . tough and enduring. In some instances "thimble" well describes the shape of the green swelling below the petal mass. Her observation about the fall foliage color is accurate, too. Roses are not noted for good color then and many drop their leaves inconspicuously. A few American species develop vivid autumn color, ones like R. nitida and R. virginiana. The Banshee plants here, while not exactly flashy, are decidedly noticeable come October. A small black and white photograph arrests our attention in that 1937 Annual: it shows Mrs. Keays' two "Albas", Clustering Maiden's Blush and Celestial. Notice that both have the Banshee foliage and, if you examine the few buds with a small lens, you will see that the calyx-tubes match two forms in the accompanying drawing. Other photographs reveal their secrets under scrutiny. Roy Shepherd described two Albas in his book, The History of the Rose, 1954. One, his "Small Maiden's Blush", he presumed to be "possibly a Rosa alba x Rosa centifolia hybrid", adding, "Some writers confused it with the Banshee Rose of Canada, but there are many points of difference." There may have been floral distinctions, but the foliage had to be the same. Both were Banshees; both balled. What is strange is the large clear photo of a rose he called "Mme. Zoutman", a Damask. It is plainly another Banshee, a very fine form. When Victoria Sackville-West wrote in the 1963 Annual about her "Roses in the Garden", I had to smile at her problem with one: And finally . . may 1 mention R. californica flore-pleno? I owe this to the kindness of Mrs. Fleischman who gave me a rooted cutting straight from California. Not knowing in the least what this was going to turn into, I stuck it into the front of the border, where within two or three years it formed a bush ten feet high and eight feet through. So, beware! It flowers madly, and is in every way a treasure, only I wish I dared move it and am wondering where it is going to stop. Graham Thomas conveniently provides an excellent portrait of her rose in Shrub Roses of Today. In his case, stock came through Mrs. Fleischman, who imported it from Bobbink & Atkins. The blooms appear to be the least double of any, so they never have the bad manners to ball in English gardens. Note the long thready sepals and the wedge-based leaflets. But we cannot lay this misidentification at the door of B & A; in the lengthy list of species roses offered in 1925-26, there is no "Californica flore-pleno".

Rose people are not alone in their attempts to pin a name on this rose that is many kinds yet none. A few years ago, a friend and I visited the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, where the herbarium is one of the finest in the country. We hoped to fix in our minds' eyes once and for all the type characters of Rosa carolina, R. palustris, and R. virginiana, but glanced through each folder the young botanist attendant brought us. Imagine our astonishment at finding in one of them four pressed specimens with unmistakable Banshee foliage, the bud clusters almost exactly like those on plants in our gardens. The folder was marked "Unidentified". You may have gathered by this time that Banshee is more than one rose. You are right, it is several. But they are so alike that even now, with the six growing here, when the season has advanced to May 15 they are next to impossible to tell apart. Only with plant maturity do the distinctions become clear. I regard the Banshees as a strain. That is, they are hybrids with the same parents, and might all have come from the seeds in a single hip. Within the strain these variations can occur: WOOD. Smooth or warty, without prickles, or, when a few prickles are present, they are red and in an infrastipular pattern; one version regularly has a cross of four stout prickles below each node. Predominantly yellow-green, sometimes aging to red-brown.

RECEPTACLE (calyx-tube; it seems strange to call a structure usually broader than long a tube). Can have any shape from thimble to cup to hemisphere to bowl, often with a constriction, or waist, about the middle, giving a double-decked look, the same as Bunyard's acorn-cup. This is a condition that occurs primarily to the initial bud in a cluster and is due to the developing carpels within. (See illustration.) All shapes do not occur on the same plant; each has its limited range of extremes. BUDS. Sepals to three times the length of the petal mass when still green, with wings (pinnules) long, thready, curling. Usually in clusters of three but can be single or as many as seven, in which case the four younger buds wither and drop off. BLOOM. Semidouble to double, two to two and a half inches. Pink, from deep bright to very pale. The more petals, the greater likelihood the flowers cannot open. In this regard our most extreme form is large, almost white; I have never seen it expand. All flowers that do, share an intense Damask perfume equal to the airborne scent of `Castilian' (R. damascene bifera) and the species Rugosas. The buds as they unfurl are often lovely, and sometimes one Banshee will regularly show good form; mostly, the bloom is muddled. Three of the Banshees here come from a garden carved out of the rectangles of Wisconsin farmland. The tall thickets that bound one long side are so dense, they make a good windbreak for the less hardy old roses that fill the inner beds. Once when the Banshees were at their peak, a visitor exclaimed, "This is the only rose garden I've ever seen that smells like a rose garden!" To give some idea of how the three are distinguished, after noting town and state (very important), I composed names like these: -- Latest; smallest; farthest from house.-- Midseason, with best form; midway in rose boundary. -- Largest; reddened pedicels, red flush on receptacles; close to house. The other details went on the yellow 5 x 8 cards I use for found rose records. The property location was added because the labels were sent to the owner as an aid in digging up the correct suckers. Only after these have grown here another few years will they become sufficiently fixed in character to study further. There is nothing of Alba in these roses. Neither in their foliage, prickleage, bud construction, nor in fruit are they alike. Only flower color is shared-a splendid example of the common urge to identify roses by their color alone. If the Banshees have been given other names, until recently, most of us have been unaware of what the type old roses should look like. Banshee does not really "impersonate" other roses. It has a strong character all its own-being sui generis in this, as Bunyard would say . . . Now that you can recognize a Banshee plant, three great questions must come to mind. How old is this Banshee clan and how long has it been in American gardens? What are the parents? and hence, what class? Has it appeared in any 19th century rose books, named? What is its real name? Parentage first. Percy Wright pointed to the likelihood that R. virginiana was elementally involved, and, observing the Banshees, this seems unarguable. Indeed, when I first saw a suckering rose in a North Carolina garden, I was certain I'd found the missing link, a five-petaled Banshee. It turned out to be a particularly fine example of Virginiana. If the strain is indeed a very old hybrid, and not some heretofore unexplored North American rose phenomenon, my candidate for the other parent is Rosa damascena. Both species have 28 chromosomes, so the cross is genetically plausible. The Damask Rose would explain the exaggerated perfume, the color, the light green foliage, and the tortured receptacle that tries to produce ovaries first on the floor of the receptacle, as proper Carolinae species do, then on the wall, where the European Gallicanae roses reproduce. No wonder the blooms ball! If some amateur hybridizer were willing to take on the experiment, the cross of Virginiana with the type Damask `Professeur Emile Perrot' might provide duplicates of Banshee. Supposing this cross to be valid, how did the two species meet across the Atlantic? Recent proof has surfaced that at least one Banshee made the trip from Europe to America before the Revolution. In Canada where the Loyalists fled in 1777 right after the Declaration of Independence, they took with them a rose brought lovingly from Scotland by the MacLeod family in 1773. Now called `Loyalist Rose', it has the unmistakable face of Banshee. By 1750, the great Swedish naturalist, Carl Linnaeus, was heavily into the importation of plants from our continent as well as others. He gave Rosa carolina its name in 1752, while the English botanist Philip Miller had the privilege of designating R. virginiana in 1759. (The latter was also called R. lucida thirty years later, a name which persisted in popularity for over a century.) Therefore, we know that Virginiana was blooming in European botanical gardens by 1759. So was Damascena. That is as much as we know. Remember the Canadian Banshee that sported? The other forms, all sharing the same foliage, might also have started out as sports. Perhaps, some time in the 18th century, our rose might have been brought over here even then mistaken for `Maiden's Blush'!

Whatever the Banshees were, they were too primitive, too close to wild roses to have been included in the catalogue-books of Rivers, Buist, or Prince. The only other non-picture book that includes all 19th century roses whether garden worthy or not is Mrs. Gore's Rose Fancier's Manual of 1838. She listed every species no matter how obscure, as well as its slightest variants. Turning to Rosa lucida, I see she calls it the "Radiant Rose". Is this because the leaves are glossy, or because the flowers are unusually bright? No mention is made of foliage sheen, yet some of the flower colors are called "brilliant"; there is a single sub-variety, the "New Radiant Rose (of Vibert)". More rewarding is the species that precedes, Rosa rapa, the "Turnip Rose", which has all of eleven sub-varieties. The Turnip Roses were North American and noted for their broad shallow receptacles that were considered "turbinate", that is, shaped like a top or the lower half of a turnip. The eleven descriptions so intergrade, with a few more Radiants thrown in, that I have come to call the batch of them "Radiant Roses". They are lost to modern botany for the type is not even referred to in the latest edition of Gray, but here is proof they existed in the 1830s. It would be cheering to report that here in Mrs. Gore, neatly, lie the answers, the names to the Banshee clan. Not so; still, one description does sound familiar. See if you agree with me:

This is about as close as we shall ever come, I believe, to a contemporary word picture of the rose known as Banshee. Be assured that it has full right to grow amid the antique Cabbages and Mosses, the White Rose of York and the Red Rose of Lancaster-not masquerading as one of them but an individual in every way, the plain little stepsister who flaunts her single charm, the best fragrance of all. When everything's said and done, Percy Wright's thoughts after much mulling over this rose haunt me: What can we conclude but that Nature is less easily fathomed than we suspect in those not-so-rare hours when we think we know it all, and that she undoubtedly hides from us many plain truths, and many more potentialities. It seems that we should not make our plans too definite, in the twilight as we are, and that we should sometimes trust to luck, trying almost any opportunity that offers. He spoke as a hybridizer but the idea applies to rose history, too. Pray let it remain that way-the rose always one step beyond our grasp.

Original photographs and site content © Paul Barden 1996-2003 |

|

Back

in 1956 I initiated a correspondence with Mr. Wright with the idea of

obtaining stock of his Banshee, but I need not have bothered. That spring,

two sets of roots came from Crosby in the farthest northwest corner

of North Dakota. The pair were labeled simply "Maiden's Blush" as they

were known locally out in that most frigid part of the country. The

following spring as I peered and poked at the unfolding leaf-buds, the

realization struck that here were no Albas at all. Already established

in the garden were Maiden's Blush, Great and Small, from Hilling's,

England, and Alba Semi-plena from Bobbink & Atkins and as a collected

plant. The Alba characters were fixed in my visual memory beyond any

question.

Back

in 1956 I initiated a correspondence with Mr. Wright with the idea of

obtaining stock of his Banshee, but I need not have bothered. That spring,

two sets of roots came from Crosby in the farthest northwest corner

of North Dakota. The pair were labeled simply "Maiden's Blush" as they

were known locally out in that most frigid part of the country. The

following spring as I peered and poked at the unfolding leaf-buds, the

realization struck that here were no Albas at all. Already established

in the garden were Maiden's Blush, Great and Small, from Hilling's,

England, and Alba Semi-plena from Bobbink & Atkins and as a collected

plant. The Alba characters were fixed in my visual memory beyond any

question.

Lambertus

Bobbink did distribute one Banshee, though. He called it Maiden's Blush

and made much of its pronounced fragrance but was not satisfied with

the name. "Maiden's Blush is probably a hybrid of Rosa alba and

therefore rather difficult to classify. We are probably correct in calling

it one of the old Damasks." He may have come closer, to the reality

of Banshee than he realized.

Lambertus

Bobbink did distribute one Banshee, though. He called it Maiden's Blush

and made much of its pronounced fragrance but was not satisfied with

the name. "Maiden's Blush is probably a hybrid of Rosa alba and

therefore rather difficult to classify. We are probably correct in calling

it one of the old Damasks." He may have come closer, to the reality

of Banshee than he realized.  LEAFLETS.

Seven, with nine on basal shoots. Pea to deep green, smooth, usually

glossy, sometimes humped, turning to light orange and rust tones in

autumn. Broadest at the outer half (obovate) sometimes with blunt rounded

tip, sometimes pointed, but always wedge-shaped (cuneate)at the base.

LEAFLETS.

Seven, with nine on basal shoots. Pea to deep green, smooth, usually

glossy, sometimes humped, turning to light orange and rust tones in

autumn. Broadest at the outer half (obovate) sometimes with blunt rounded

tip, sometimes pointed, but always wedge-shaped (cuneate)at the base.

Was

it ever illustrated by the great portrayers of roses, Mary Lawrance,

Henry Andrews, Pierre-Joseph Redoute? If Miss Lawrance engraved it,

and if prints of her plates were available, I doubt that we could recognize

it as distinct. Her roses have a most frustrating sameness about them,

and since they are only that, plates published in portfolio form without

explanatory text, and so rare that very few libraries own sets, her

work is ruled out. While Andrews' Roses is remarkable because

he not only made his own drawings and engravings but wrote his own text,

the only Damasks he bothered with were the repeating Portlands. Redoutes

plates often need repeated scrutinies

before they snake sense; the four or five perusals of original copies

have so far revealed nothing.

Was

it ever illustrated by the great portrayers of roses, Mary Lawrance,

Henry Andrews, Pierre-Joseph Redoute? If Miss Lawrance engraved it,

and if prints of her plates were available, I doubt that we could recognize

it as distinct. Her roses have a most frustrating sameness about them,

and since they are only that, plates published in portfolio form without

explanatory text, and so rare that very few libraries own sets, her

work is ruled out. While Andrews' Roses is remarkable because

he not only made his own drawings and engravings but wrote his own text,

the only Damasks he bothered with were the repeating Portlands. Redoutes

plates often need repeated scrutinies

before they snake sense; the four or five perusals of original copies

have so far revealed nothing.